Lots of info, loosely held

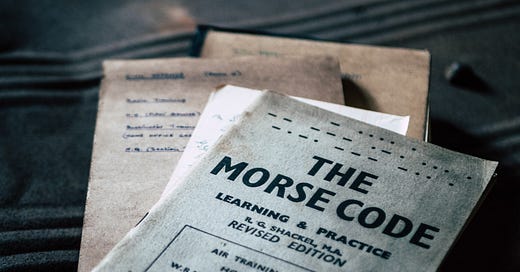

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was a painter in the eighteenth century. He painted portraits of solemn-looking men mostly, which perhaps without intending to, conveyed information about his world. You might know him better as co-inventor of the Morse Code. The code of dots and dashes replacing letters and numbers that he developed in 1838 along with Alfred Vail enabled information to be transmitted over the electric telegraph, which Morse had invented a few years earlier. International Morse Code was used in World War II and in the Korean and Vietnam wars, and by the shipping industry until the early 1990’s. The unmistakable beep-be-beeps of Morse code being tip-tapped across the world turned out to be a far better way of communicating information than paintings.

A hundred and ten years after Morse, Claude Shannon was publishing his theory of information. Shannon had already showed how the if/then logic of algebra could be represented as one’s and zero’s by opening and closing switches, laying the ground work for the modern digital computer. His latest work showed that all information channels have a maximum bandwidth that can’t be exceeded and that with the use of mathematics, a signal could be reliably received despite the noise that comes along with it.

This history of transmitting information tells us a thing or two about how we receive and process information ourselves. As the amount of information available to us is more than ever before and increases every day, we need to think seriously about our relationship with information.

You probably knew this already, but a zettabyte is a number with 21 zero’s after it. In 2020 the World Economic Forum estimated the amount of data in the world to be 44 zettabytes. And then Seagate, the data storage company, said that by 2025 there will be 175 zettabytes of data in the global datasphere. That’s a lot of data. More bits of data than all the grains of sand on earth or all the stars in the sky. More data than any human brain can handle.

Your brain can process 11 million bits of information every second, but your conscious mind can handle only 40 to 50 bits of information a second. That’s the limit of your bandwidth. Shannon tells us that we just can’t take any more than that. But that’s ok. We shouldn’t try to take in more information. More information is not the answer. Better information is.

Better information is more meaningful information. It’s the signal that you're actually trying to detect among all the random unwanted noise that interferes with the signal. If you’re old enough to remember recording songs from the radio onto cassettes, then you’ll remember the crackly hiss and the DJ speaking over the start and end of the song that frustrated you. Compared to listening to Spotify streaming over broadband nowadays, it was an experience of low signal, high noise. Lots of what you didn’t want to hear, and not enough of what you did want. But that’s an easier situation to deal with because you very obviously know the difference between the signal and the noise. What about when all the information is high definition crystal clear? How do you tell what is meaningful and what isn’t then?

The answer might come from a quieter time, one with vastly less information. Back in the eighteenth century, Thomas Bayes, the English statistician, philosopher and Presbyterian minister, created a theorem that describes the probability of an event based on prior knowledge of conditions that might be related to the event. And now, in our complex, fast-moving world, we can take apply the same idea without even knowing how to do the maths.

The chances of our mental models of the world being right first time based on incomplete information is very low. We should accept that. Instead of trying the impossible task of filtering the information to give us the one true right answer, we should accept information that gives us some degree of confidence in what we understand, and we should know that we’ll probably need to update that opinion, and our confidence in it, when we get more information. This is Bayesian thinking. It’s about accepting that we can’t know for sure and that it’s ok to change our minds. It’s about thinking in probabilities.

In a world of information overload, our attempts to deal with all that data should not be to seek out the right information, and form one right opinion, and hold it forever. That’s a short-cut to being out-of-date and certainly wrong. Our world changes too quickly for that. Instead, we have to be open-minded. Open-minded about how correct the information we’re receiving is, open-minded about taking onboard new information from different sources, changing what we think, feeling more or less confident in our opinions, adding more information, ignoring things we previously thought correct.

This is how we reshape our relationship with information. No longer are we the seekers of the single truth, we are the receivers of information and we can choose whether we consider it meaningful or useless, signal or noise.

Lots of info, loosely held.